Before They Were Rock Stars

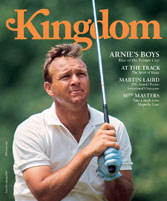

Kingdom Magazine, SPRING 2014

Pennsylvania’s 84 Lumber Classic tournament fell on a bad date in 2004—one week after the Ryder Cup (held in Michigan) and one week before the American Express Championship, in Ireland. To help attract top golfers, the tournament’s sponsors hit on a great idea: they chartered two 747s customized with first-class-only seating and offered direct transport from Western Pennsylvania to Ireland for all the players and their families. It’s a flight Walter Hagen would have enjoyed.

In Hagen’s day, professional golfers weren’t even allowed into clubhouses during tournaments, a fact of life that greatly irked the flamboyant pro. Today, of course, touring pros are treated well, often enjoying their own clubhouse entrances, use of private members’ lockers during tournaments and numerous other perks ranging from basic niceties like free dry cleaning to luxury pluses like the aforementioned flights. My, how times have changed.

Until the end of the 19th century, competitive golf was played exclusively by amateurs. The first professional golfers—those who tried to make a living by playing in various tournaments—were former caddies, greens keepers and club pros, and were not considered to be the social equals of the amateur golfers who belonged to private clubs. Because purses were so small, these players had to supplement their income by giving lessons, crafting clubs and even caddying. Mostly blue-collar players, they were constantly on the road bouncing from tournament to tournament, trying to manage their travel, food and lodging expenses. If they didn’t make a cut, they didn’t collect a paycheck, putting their ability to make it to the next tournament in question. And even if they did make it to the match, they weren’t allowed to enter the clubhouse at the private courses where they competed.

One of the men who changed that was Walter Hagen. Born in 1892 in Rochester, New York, Hagen came from a working-class background with a blacksmith for a father. Dubbed “Sir Walter” by his business manager (former newspaperman Robert Harlow), Hagen skipped a tryout for baseball’s Philadelphia Phillies to play in the 1914 U.S. Open, which he won by defeating the likes of amateur greats Francis Ouimet and Chick Evans.

His continued on-course performance is well-documented—including his 11 major championships, just behind Jack Nicklaus (18) and Tiger Woods (14), four [British] Open victories and five PGA Championships, to name a few—and thanks to Harlow he developed a reputation off course as a partier who could drink and dance all night then show up the next day ready to play. But there was another, more serious aspect to Hagen, and it came to the fore in 1920 at the [British] Open in Deal, Kent.

Finally fed up with not being able to enter the clubhouse, Hagen hired a Pierce-Arrow car and chauffeur and had the auto parked in front of the clubhouse, where it served as his personal changing room—and where it raised eyebrows. He wasn’t the only pro to pull that stunt (Henry Cotton and others often changed in their cars as well at the time), but Hagen’s profile and the stature of the event ensured it was noticed.

Back home in the States, things were getting a bit better, albeit slowly. As early as 1914, historian Herb Graffis held that Hagen reportedly led a number of pros into the clubhouse at Midlothian during the U.S. Open, though they were hardly welcomed with open arms. The first truly open doors for the pros came in 1920 at the Inverness Club in Toledo, Ohio. When Inverness was chosen to host the 1920 U.S. Open, club co-founder and golf industry heavyweight Sylvanus P. Jermain decided it was time for a shift. A player, club designer, golf innovator (the Ryder Cup was partly his idea) and entrepreneur, Jermain convinced the membership to open the doors to the touring pros. Going the extra mile, Inverness members sourced accommodations for players and even provided cars for their use—a complete about-face from the way things had been done. When the U.S. Open returned to Inverness in 1931, Hagen led the other players in collecting enough money to purchase a clock as a token of thanks for the hospitality in 1920. The clock still stands in the clubhouse lobby today. Sadly, Inverness was the exception; and in England, especially, the clubs were still holding fast to tradition.

At Royal Troon in 1923, having been denied access to the clubhouse during the tournament, Hagen later refused to enter it to accept his runner’s-up trophy. Additionally, he arranged for a picnic on the front lawn and celebrated the day in full view of the members. Similar treatment persisted all over the country and reached the very heights of the game, as showcased by Michael K. Bohn, author of Heroes & Ballyhoo: How the Golden Age of the 1920s Transformed American Sports. In his book, Bohn mentions a 1928 lunch at Royal St. George’s, which indicated attitudes were changing even if customs were not:

“When [Hagen] and Gene Sarazen sat down for lunch with the Prince of Wales, their presence ruffled the club’s staff. ‘Golfing professionals are not allowed in the dining room,’ they whispered to the prince. ‘You stop this nonsense,’ the prince retorted, ‘or I’ll take the “Royal” out of St. George’s.’”

Despite shifting opinions among the likes of the Prince (who later became King Edward VIII) change was slow to come, as Cotton recounted to the Associated Press in 1977.

“For many of those early years, the professional was looked upon as little more than a lackey and held in disdain by the club members,” he said. “We weren’t allowed in the clubhouse. We had to change clothes in the caddie shop, hanging them on nails and laying them out on benches. They were always on the floor when we got back. We had to eat in the kitchen.

“I’ll never forget 1930 when [Bobby] Jones came to Hoylake in pursuit of his Grand Slam. He was accompanied by Leo Diegel, a professional. After a practice round, Jones was swept into the upstairs trophy room by exuberant admirers. He looked around and said, ‘Where’s Leo?’ ‘Sorry, Mr. Jones,’ he was told. ‘Professionals are not allowed in here.’ So Jones took his drink plus one for Diegel and the two sat on the front steps to finish them.”

Lobbying efforts by the likes of Hagen and Cotton, the opinion of luminaries like the future King of England and bold moves from clubs like Inverness eventually tipped the balance toward the pros, and the dominoes, as they say, began to fall.

But even as golf entered the era of Sam Snead, Ben Hogan, Byron Nelson and the like, and professionals began to enjoy enhanced social status, purses were slow to grow and so the life of a pro continued to be difficult. Hogan kept a day job as an assistant pro at Century Country Club in New York (and later as head pro at Hershey Country Club in Pennsylvania) even when he was climbing the money list as a professional golfer. Likewise, many of the other touring pros took work on the side to supplement life on tour.

The next shift in the evolution of the touring professional wouldn’t come until after WWII, but this time it wasn’t a person like Hagen leading the charge for change, it was a device: television.

Lew Worsham won the first golf tournament to be nationally televised, 1947’s Tam O’Shanter World Championship of Golf, which was also the sport’s first $100,000 tournament. Worsham holed a wedge from 104 yards for an eagle-2 to take victory from Chandler Harper by one shot, and a sizeable ABC audience saw it happen. It was just the beginning. Televisions became cheaper (and thus more popular), and when color models hit the shelves in the late 1950s they were just in time to catch golf’s newest superstar: Arnold Palmer. Like Hagen, Palmer was a blue-collar champ who won over the masses with good looks and a fearsome game. Helped by TV, Palmer’s fame eventually resulted in larger television audiences, more sponsors and richer purses. Still, the money wasn’t exactly great, and it wasn’t uncommon for young pros like Gary Player to sleep in bunkers at night as they tried to make ends meet.

But when it changed—and boy, did it change—it’s as if the money appeared overnight. According to Forbes, in 1970 the total purse for the PGA TOUR was $5.5 million. Four decades later, in 2012, it was nearly $280 million. The biggest upswing came following 1996, which not coincidentally was the year Tiger Woods made his PGA TOUR debut.

Tiger’s impact on the game has been huge in terms of both performance and marketing, and as purses and endorsements grew to stratospheric levels in the wake of his appearance, the touring pro’s social status shifted yet again: What had started as a hierarchy with club members at the top and pros on the bottom, and then achieved a kind of level in the mid 20th century, was now tipped firmly to the side of the pros in terms of money and benefits. Today, rather than turning them away, clubs and tournaments compete for professionals’ attentions and the top players on TOUR earn the sort of reward their TV ratings merit. The money means top players can free up time as they fly by private jet directly from home to tournament, or tournament to tournament.

But for as much as the pros have gained, there are those who believe something might have been lost as well. “In the early days, we often hitch-hiked to tournaments,” said Doug Sanders, the man who agonizingly lost the 1970 [British] Open at St Andrews with a missed short putt. “There was not much money on offer but we were all friends. Today all the top players fly to tournaments in private jets, in their own little bubble, but they live in a smaller world than the one we occupied. They can never have the fun we had.

“In those days, our main aim was friendship. I’m from the South and when I was playing on Tour I’d walk down the street sometimes and I’d always be stopped by someone who wanted to talk about what I’d been doing. I didn’t mind at all—in fact I loved it. It was always friendly and no hassle at all. I’m not sure the modern players would put up with that. When I was on TOUR we knew everyone straight away and we travelled by car from tournament to tournament, maybe three to a car.”

Tony Jacklin, 1969 [British] Open champion and 1970 U.S. Open champion, has similar memories.

“Of course, everything was so different back in the mid-1960s when I first went out on the European Tour. I was an assistant at Potters Bar [a golf club just north of London] and had to take time off to play in tournaments,” he said. “But I had a good boss, Bill Shankland, who indulged me because, I suppose, he thought I had talent. Whatever happened on Tour, though, I had to be back in the pro shop by the weekend without fail. The tournaments used to end on Friday, when we’d play 36 holes, and we’d then drive home through the night. Today, not only is the money colossal but the whole atmosphere seems a little impersonal. Still, good luck to them. The modern players are terrific ambassadors for the game and the golf they play is way beyond my comprehension.”

And it’s tough to argue with the money, which is benefitting some of the old guard as well as the newer players. Palmer, who first topped the money list in 1958 with earnings of $42,607, made more than $36 million from the game in 2012, putting him at the No.3 spot in terms of earnings (only Phil Mickelson and Woods ranked higher). Player and Nicklaus were also in the Top 10, and though this money is clearly from off-course endorsements and their own business prowess, it’s indicative of the massive shift for pros.

The changes in the game since the days of Hagen and Cotton have been tremendous, and whatever one’s perspective on the current luxuries enjoyed by pros it’s obvious that they’re far better off than they were at the professional game’s outset, and much of that is down to Hagen. At a 1969 dinner honoring him, Arnold Palmer raised his glass and offered a toast: “If it were not for you, Walter, this dinner would be downstairs in the pro shop and not in the ballroom.”

Better than that: it wasn’t in the parking lot.