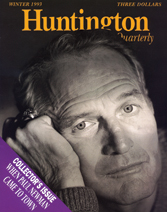

An American Icon

Remembering the late Paul Newman and his visit to Huntington in 1966

Huntington Quarterly, Autumn 2008

An early September morning in 1966 found my father and Paul Newman driving down Eighth Street. They were hungry. Their original plans were to head straight for Wayne County, but on this morning they had a hankering for some sweet rolls.

My father pulled his Ford station wagon into the Torlone’s Bakery parking lot and got out of the car. Newman stayed behind.

“Good morning, Mr. Houvouras. How are you?” Mrs. Torlone asked.

With that, a young woman from behind the counter inquired, “Are you Andy Houvouras?”

“Yes, I am,” he replied.

“Is Paul Newman really up at your house?” she asked with trepidation.

“Well, yes, he is...”

“I don’t believe it!” the young woman shouted.

“What do you mean?” Mrs. Torlone interrupted with her thick Italian accent. “Last night I see him with Mrs. Houvouras on the television. What you so excited about? He’s a man just like your husband.”

“The hell he is,” the young woman countered.

I was only 2 years old when Paul Newman came to my home. Of course, I have no personal memories of that visit 42 years ago, but over time I have heard the stories, one and all, from my family. It is something they will never forget. I wish I could say the same.

Newman came to Huntington in September of 1966 for three days to prepare for his role in the movie Cool Hand Luke. He wanted to master a dialect, an accent if you will, that conveyed that his character was from a small town in rural Appalachia. And, as part of that preparation, he needed a West Virginia contact to introduce him to some people in the area.

Newman was told to call on my father through a mutual friend — Sargent Shriver, then head of the Peace Corps and a major player in President John F. Kennedy’s run for the White House. Shriver’s secretary set it up, and in early September my father was given notice that the actor would be “in touch that evening.”

My father remembered the call he received that night with uncanny clarity.

“Andy? This is Newman,” the actor said casually. “Sarge Shriver tells me you might be able to help me out.” The two chatted for a few minutes about his upcoming movie and politics and then got down to the business at hand.

“When I land at the airport in Huntington I’ll be incognito,” Newman explained. “I’ll be wearing dark sunglasses so no one will recognize me.”

Day 1: When Eastern Air Lines found out that Paul Newman was on board, it sent word to Huntington’s Tri-State Airport. When my father arrived to pick him up, the actor walked off of the plane and was hit by a sea of floodlights. The airport workers shouted, “Paul Newman!” The disguise hadn’t worked.

My father then drove Newman to our house where my mother and six brothers and sisters had been waiting with anticipation. When my father walked through the front door with the movie star, the family was flustered. But their nervousness quickly vanished as Newman was, in their own words, “very down to earth.”

So earthy in fact that he sported a pair of raggedy old corduroys that didn’t quite fit his Hollywood persona. It was ironic that my parents, who wanted to make a good impression, had forbidden my oldest brother Drew from wearing a pair of corduroys that were nearly identical to Newman’s.

“He was very charming,” my mother recalled, “and so nice to everybody. He was easy to get along with, and you could feel right at home with him immediately.”

The first thing Newman did upon arriving at our house was to ask to use the telephone. “I want to call my broad,” he said.

“Oh, Lord,” my father remembered thinking to himself. “He’s got a gal in every town.” But instead, he was calling Joanne Woodward, his wife and favorite leading lady.

After some casual conversation in the living room with the entire family, Dad drove Newman to the Uptowner Inn, where he checked into the downtown hotel for three nights.

Paul Newman was born and raised in Cleveland, Ohio. The son of a successful sporting goods store owner, he never had a taste for business and, upon graduation from high school, enrolled in Kenyon College where he studied English and played football. He left college to enlist in the Navy after the outbreak of World War II and served three years as a radioman on a torpedo plane in the South Pacific. He then returned to Kenyon where he graduated, as the school yearbook noted, with “Magna Cum Lager” honors. His thirst for ale was notorious.

His introduction to acting was purely happenstance. While out one evening with some of his Kenyon football teammates, Newman and company got into a barroom brawl and, subsequently, were kicked off the squad. Bored and having nothing to do, he started acting in school plays. From there, he went on to summer stock in Wisconsin and Illinois.

But his father’s death in 1950 put his acting career on hold when Newman returned to Cleveland to manage the family business. It wasn’t long before Newman grew weary of the job. He eventually sold the business and enrolled in the Yale School of Drama, where he earned a master’s degree.

“It’s not that I ran to acting,” Newman said, “but away from business.”

In 1958, he married Academy Award-winning actress Joanne Woodward. Their celebrated relationship would become one of enduring strength over the years. Married for 50 years, he called her “the last of the great broads,” telephoned her every night when on the road and described their marriage as the best thing in his life.

Newman has more than 50 movies under his belt, the most noteworthy of which are Somebody Up There Likes Me, The Long Hot Summer, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, The Hustler, Cool Hand Luke, Hud, Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid, The Sting, The Verdict, Absence of Malice, Blaze and The Color of Money.

But, Newman would never say which is his favorite.

“It’s like having 50 children and being asked which one you like best,” Newman told me in an exclusive 1992 interview about his time spent in Huntington. “It’s also very complicated. There were some pictures which were very successful and the roles didn’t require much work. Others weren’t very successful but really demanded a tremendous amount of concentration. And, because I was able to make them better they were more laudable somehow.”

It was The Color of Money, co-starring Tom Cruise, that finally earned Newman his first Oscar, some 20 years after the release of Cool Hand Luke — the movie that should have produced the first in a long line of Academy Awards for the actor.

Day 2: Dad joined Newman for breakfast at the Uptowner before the two set out on their first day of work. They drove to Chesapeake, Ohio, and met with a gentleman who spoke with a subtle accent. Newman brought along a tape recorder and spent time simply conversing with the gentleman, all the while absorbing his mannerisms and dialect.

From there it was back to the house for lunch, as Newman was trying to keep a low profile while in town. But that wouldn’t last long. It would only be a matter of time before news got out and the actor would be forced to graciously consent to some unwanted publicity.

After lunch, Dad wanted to show Newman the city, and the two did some shopping in downtown Huntington. What shops they visited and who they encountered has been lost with time — both my father and Newman confessed to having trouble remembering things.

It was during their drive around town that Newman told my father he liked the script for Cool Hand Luke. “It’s unusual,” he said. “It’s one of the best I’ve read in years.”

That afternoon, the actor spoke to a drama class at Marshall University. It was then off to Guyan Country Club where he joined my parents and some of their friends for a late dinner.

While walking down the steps to the main dining room, Newman was spotted by the bartender, Leo. Ironically, on the television at that moment was The Hustler which starred Newman.

“Man, that can’t be you coming down the steps!” said Leo in amazement. “You’re on TV!”

At the dinner table, Newman was approached by a woman who wanted to get a closer look at the movie star.

“I remember that he tried to stand up to shake her hand,” my father recalled, “but he was kind of pinned in and was straddling his chair. As the lady walked back to her table, she said, ‘Oh, he’s so short.’ And Paul yelled across the room, ‘Damn it lady, I’m straddling this chair!’ He had a great sense of humor.”

After dinner, an interview was set up at the country club with Bos Johnson from WSAZ. The station then photographed the actor leaving Guyan with my mother. For my mom, this would be her shining moment — seen by thousands on television being escorted by Paul Newman.

When Newman and my parents arrived home for an after-dinner drink, a group of women was standing in the driveway. My father, in an attempt to keep the women from harassing the star, walked up to them and politely asked, “Excuse me, do I know you?” With that, one of the women pushed my father aside and said, “Get the hell out of the way!” Newman was immediately surrounded.

“To get him out of the jam,” my father recalled, “I went into the house and then came out and yelled, ‘Long-distance telephone call, Mr. Newman.’ As he entered the house, he turned to me and said, ‘Thanks a lot, Andy.’”

It was in our living room that evening when the actor ripped opened his first Budweiser of the trip and talked candidly with the family.

“One of the things I remember most is Paul telling stories in the living room after dinner,” my brother Rick, then 17, recalled. “Everyone would gather around and just listen. I also remember that all the women in the family had a strange look in their eyes the entire time he was here.”

A strange look, indeed. My mother, in particular, would later describe him as the best-looking man she had ever met. And my sister Mary, then only 12, said of the time, “I didn’t quite know who he was because I was still watching Disney movies. But, I quickly learned about men because he was so good-looking.”

He told stories about his days in Kenyon College. When money was tight, he bought a coin laundromat, and to entice people to come in he would put in a keg of beer on Saturdays and give it away.

“People would get so drunk that they would ride in the dryers and I would do their laundry and charge them twice,” Newman told the family. He also showed the family which shots he had made from The Hustler, and which shots were staged by pool sharks.

“He was very entertaining,” my brother Rick recalled. “He was a great storyteller, and he wasn’t pretentious at all.”

When Newman finally returned to the Uptowner late that evening, a group of drunken Marshall students partying at the hotel ran into the actor and said, “Hey, you know what? Paul Newman is staying here!” And Newman replied, “Yeah, I heard that,” and walked into his room.

In 1968, Playboy magazine named Paul Newman the nation’s number one male sex star. For all intensive purposes he was, as People magazine might have said today, the “Sexiest Man Alive.”

For Newman, it was his striking good looks that had been his greatest friend and foe. When he first broke onto the movie scene, it was his appearance, in particular his famous baby blue eyes, that often gained him notoriety. But Newman, never tolerant of such superficial exposure, has always downplayed such praise. And, in an interview with Playboy in 1968, he spoke out on the subject.

“You break your ass for 18 years working at your craft, and a lady comes up and says, ‘Please take off your dark glasses so I can see your blue eyes.’ If I died today, they might write on my tombstone: ‘Here lies Paul Newman, died at the age of 43, a failure because his eyes turned brown.’ I’d like to think there’s a mind functioning somewhere in Paul Newman, and a soul, and a political conscience, and a talent that extends beyond the blueness of my eyes.”

Over the years, Newman has worked diligently to foster the qualities he detailed in that interview. Because of his political conscience, he found himself involved in a number of controversial issues over the last five decades.

In 1963, he demonstrated his support for the civil rights movement by taking part in the March on Washington. Ever meticulous about preparing for his roles in film, he threw the same time and effort into researching the political issues of the day. For example, he took time off from work in 1962 to visit Gadsden, Ala., the site of several racial incidents in the South, as part of his study of the civil rights issue. He spoke out against the country’s role in the Vietnam War and the proliferation of nuclear weapons long before it was fashionable in Hollywood.

“I think the issues today seem obvious,” Newman told me in 1992. “Drug prevention (his son Scott died of a drug overdose), the deficit, and choice. But, above and beyond that is a larger issue, which is the deification of the individual at the expense of the community.”

His political views often won him disfavor with the public. In 1968, he told Playboy, “People sometimes come up to me and say, ‘Why take a chance? It can’t help you professionally to get involved.’ My response is, ‘Kiss off!’ Of course it can’t help me. If you speak up you’re going to make enemies. But a man with no enemies is a man with no character.”

Newman’s character is reflected in the various causes he embraced over the years. When asked which things in his life he is most proud of, he told me, “I guess it’s that I’ve managed to get my fingers into a lot of pies. I’m very proud of my family (he has five children), my automobile racing and the political aspect. And, I’ve been able to help some people with my food companies.”

In 1982, the actor and a friend began marketing Newman’s Own Salad Dressing. It was a huge hit.

What followed next was Newman’s Own Popcorn, Newman’s Own Spaghetti Sauce, Newman’s Own Lemonade and more. They would all win favor with the consumer. In fact, in the last 26 years his food businesses have generated a staggering $250 million in profits, aiding some 4,000 charities. That’s a lot of fingers in a lot of pies.

An example of the work being done with that money is Newman’s “Hole in the Wall Gang Camp,” founded in 1988 and named after the infamous bandits in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. The camp is a summertime refuge for children suffering with cancer, leukemia and other serious illnesses. He put up $8 million of his own money to fund the free camp located on a 300-acre site in the hills of northeastern Connecticut.

“It occurred to me,” Newman said, “how rewarding it would be for someone of privilege to provide a few weeks of happiness for the young people where they could get together and establish common bonds under the umbrella of an old-fashioned camp experience, the likes of which I remember so vividly from my childhood.”

The camp hosts some 600 children each summer and offers state-of-the-art medical facilities and an abundance of activities. Over the years the camp grew to include 11 locations around the world attended by some 15,000 children annually.

Day 3: After leaving Torlone’s Bakery, my father and Newman picked up West Virginia politician A. James Manchin and headed out to Wayne County where the actor spent the day in the homes of several local residents.

During one of their stops, a woman asked Newman, “Why are you with Andy Houvouras?”

Newman responded by saying, “Andy is a good friend of Sarge Shriver and so am I. He told me to look Andy up if I came to West Virginia.”

But, on the way out of the woman’s home, Newman, always ornery, turned to my father and said, “If I had thought about it, Andy, I would have told her that we used to go out chasing women together in the Navy.”

That evening, Newman joined my family for a quiet dinner at home. But, little did they know what lurked in the woods.

Having heard the movie star was at our house, my brother Drew’s girlfriend, Georgeann Linsenmeyer, and a group of her friends from Marshall had tracked through the muddy woods behind our house and were staring at Newman through the dining room window as he ate dinner. “I was so embarrassed,” my brother Drew recalled.

After dinner, my parents invited some of their friends up to the house to meet the actor. Among the guests were Tom and Eleanor Conaty and Steve and Edda Jacobson.

One of the highlights of the evening occurred when Mrs. Jacobson asked Newman, who had been married to Woodward for eight years, if he had ever been tempted by the glamorous movie stars in Hollywood.

“Why go out for hamburger when you have steak at home?” he replied.

The highlight of the visit for my sister Amy, then 8, also took place that evening. After the guests had gone, Newman retired to the living room, cracked open another Budweiser, and began telling more stories.

“He was sitting down by the fireplace and I remember walking up behind his chair,” my sister recalled. “And then, for some reason, I rubbed my fingers through his hair. I guess I did it because I had heard all these women talking about him and I had seen all these women outside the house. I thought to myself, ‘I’ll bet they’d all like to do this.’” Afterwards, Newman sat her on his lap and kissed her on the cheek. When my sister smiled he began calling her “Fang” because she was missing her two front teeth.

In the midst of one of his stories, Newman discovered that he had consumed the last of his precious Bud. However, my brother Drew came to his rescue.

“My girlfriend’s family had a Falls City beer distributorship,” my brother recalled, “and we went out and got him a 12-pack. It wasn’t Budweiser, but he liked it.”

Afterwards, my brother drove Newman back to the Uptowner and the two passed some time in his hotel room swilling Falls City Beer and discussing history. “He later sent a picture of himself to each of us, and on mine he wrote, ‘To Drew, a graduate Magna Cum Lager. Best, Paul.’ We drank quite a few brews that night.”

Newman had always been his own man. Never one to play the glamour game with the rest of the movie industry, he always bucked the trends. While most film stars made their homes in Hollywood, the Newmans chose the serenity of a 200-year-old carriage house in Westport, Conn. Always protective of his privacy, Newman preferred to stay out of the limelight, often shying away from public appearances. You can count the number of interviews he granted over the years on one hand.

At the start of his career, when he was up for an important role in On the Waterfront, he was kicked out of legendary film producer Sam Spiegel’s office for refusing to change his name. Spiegel, we now know, had gone by the name of S.P. Eagle when it was not “convenient” to be Jewish in Hollywood.

“I was in his office,” Newman told Esquire magazine in 1989, “and Spiegel said, ‘Have you ever thought about changing your name? It’s not phonetic.’

“And I said, ‘You mean it sounds faintly Jewish?’

“Yes, yes,” Spiegel responded.

“‘Well, I have thought about changing it to S.P. Newman.’ That was the last conversation I ever had with him.”

While most in Hollywood were driving around in Rolls-Royces and limousines in the late 1960s, Newman was behind the wheel of a souped-up Volkswagen. The car, which sported a Porsche engine and Dunlop super sport tires, was most likely the vehicle that first got him involved in professional automobile racing. He even went so far as to show up in the car at a lavish black-tie gala for Princess Grace.

Newman dressed the part of the non-conformist as well. You could usually find him in blue jeans, a T-shirt and an old pair of loafers. Over the years, he was a regular on the “Worst Dressed List.”

“I’ve never been terribly concerned about status,” he told Playboy. “I’ve always felt there were certain unnecessary things about Hollywood: public relations, being seen, having your picture in the newspaper, the whole bit. I’m not your typical movie star,” he said with a smile.

Day 4: On the morning of Sept. 15, 1966, Paul Newman checked out of the Uptowner Inn. My father then drove him to St. Joseph’s High School where he introduced the star to some of the nuns. It was quite a scene as the women in black and several students surrounded the actor in an attempt to get autographs. But, in the middle of it all, one elderly nun walked up to the large gathering and inquired, “What’s all the commotion about?”

“This is Paul Newman, sister,” one of the students replied. With that, the nun extended her hand to the actor and said, “So Mr. Newman, what do you do for a living?”

When my parents left the school, they brought along my sister Anne, then 15, to accompany them to Tri-State Airport. Along the way, Newman noticed that his shirt was torn, and so my father stopped off at Huntington Plating (our family business) so he could change. As he got out of the car, the actor overheard my sister say, “I would love to have that shirt.”

After changing inside, Newman turned to my father and said, “Andy, I don’t normally do things like this, but if you think Anne would like it...” He then laid the shirt down on a desk and wrote on the back of it: “To Anne. If I was twenty years younger - Paul Newman.” For years, my grandmother wore the shirt as a bed jacket in our house. Eventually it was returned to Anne who embroidered the words on the shirt so they would last forever.

When they arrived at the airport, a crowd of fans and reporters greeted Newman. He graciously signed some autographs, granted an impromptu interview to The Herald-Dispatch and then checked his luggage through.

Finally, just before boarding, he thanked my parents and kissed my mother good-bye. He then left for Los Angeles.

Cool Hand Luke was released in Autumn 1967. Set against the backdrop of the rural South, the film depicts the trials and tribulations of Lucas Jackson, a war hero from rural Appalachia, arrested and sentenced to two years on a chain gang for cutting the heads off parking meters while on a drunken binge.

Much like Newman himself, Luke is a rebel, an individualist who cannot come to terms with society’s regulations. Luke grows frustrated by the rules being laid down by the “bosses” of the world and defiantly scoffs at his oppressors. It is his unwillingness to conform to the community, in and out of prison, that is his ultimate crime.

“In the most legal sense, Ol’ Luke had broken the law, however unmaliciously,” Newman told me in 1992. “But, I think the thing that made him was his individualism and his struggle for freedom. He used those to somehow knit the community together – which is precisely what is needed today.”

Luke’s struggle served to unite the other prisoners. He lifted their downtrodden spirits with his irreverent and spontaneous approach to life.

“I can eat 50 eggs,” he proudly boasts one evening in the jailhouse. “No one can eat 50 eggs,” another prisoner asserts. However, with every dollar in camp bet against him, Ol’ Luke proved them wrong.

“I liked his scenes of delight more than I did the ones that were emotional or tough,” Newman recalled. “I liked Luke best when he was just having fun.”

Cool Hand Luke is a film of great accomplishment. Adapted from the book by Donn Pearce, it is beautifully written. It is further enhanced by Conrad Hall’s color photography – brilliant for the time – and Stuart Rosenberg’s masterful direction. Finally, the music by Lalo Schifrin is some of the most moving and appropriate in American film. Critics heralded the movie and Newman’s performance as Oscar material:

“If Cool Hand Luke weren’t so well made, it could have become just another chain-gang picture. As Luke, Newman gives his strongest and most appealing performance to date.”

Commonweal, Dec. 1, 1967

“Paul Newman is at his best in Cool Hand Luke.”

The New Yorker, Nov. 11, 1967

“A picture of chilling dramatic power.”

TIME, Nov. 10, 1967

“It’s going to be a distinct problem, as the time of award ceremonies approaches, to decide which male actor has given the best performance in films this year. There are already leading candidates in Rod Steiger and Sidney Poitier (In the Heat of the Night), and Warren Beatty (Bonnie and Clyde), and now the problem is further complicated by Paul Newman’s stirring performance in Cool Hand Luke, a film as beautifully executed as any made this year.”

Saturday Review, Nov. 11, 1967

Both Newman and the film earned Oscar nominations in 1967, but neither won. In the Heat of the Night took honors as the year’s best film, and Rod Steiger took home the award for best actor. As it often happens, the Academy missed the boat.

On Sept. 28, 1966, my mother received a package postmarked from Beverly Hills. Enclosed was a small piece of stationery that read:

Dear Pat:

Am richer by far because of my acquaintance with you and that crazy husband of yours and those rather attractive children. Leave for location in two days and will be up there for about seven weeks. I certainly hope you’re not drunk as much. I had a hell of a time keeping up. I have told my wife about the bad influence you were on me but nothing of our escapades.

All the best,

Paul

Enclosed were six black-and-white photos, one for each of my brothers and sisters, all with personally signed messages. Unfortunately, I was the only one who didn’t receive a photo. I was only 2 years old. Finally, some five months later, a larger package arrived at our house with the enclosed letter:

Dear Houvourases:

I do not basically consider myself an ungrateful, discourteous type of person and for some time now I have been sniffing idly about for something, a remembrance perhaps, a token, that might be usable by all. I hate table cigarette lighters, engraved martini pitchers, cases of whiskey, glassware, parachutes and that sort of thing.

I came across this, which came out a couple weeks ago actually. I hope you wear it in good health. It was a good time for me.

With considerable affection,

Paul

Enclosed was one of the first portable Sony television sets ever made. The TV has since passed through every hand in the Houvouras family, and, needless to say, we still have it. Years after his visit, Newman still remembered my family and the people of Huntington with affection.

“What I remember most is how comfortable I was made to feel in Huntington,” he told me in 1992. “Everyone was extraordinarily helpful. They took good care of me.”

Some 42 years have passed since Paul Newman walked the streets of Huntington. He left behind a handful of memories for those who were fortunate enough to have met him.

Looking back, I suppose I envy my family for the time they shared with the actor. He was an intriguing character – one I would like to have known.

When I first spoke with Newman for this article, everything I had been told about him rang true. He was genuine, humble and down to earth. When I asked him what things he was working on today, he said, “My personality.”

“What aspect of it?” I asked.

“I’m trying to lighten up a little,” he responded with a laugh.

His voice was soothing and cool, his words carefully chosen. What impressed me most about Paul Newman was his mind, its capacity and how well versed he was on a number of different issues.

Having the unique opportunity to examine his work, both as an actor and a humanitarian, my perceptions of the man changed. Perhaps the greatest thing I gained from my study of Paul Newman was the realization that those notorious blue eyes, for which he is best known, were indeed his greatest gift – however, not for their richness of color but, rather, for their sharpness of vision.

Paul Newman passed away on Sept. 26, 2008, at his Westport, Conn., home after a long battle with cancer. He was 83. Approximately one year before his death he learned of the fire that destroyed the Huntington Quarterly offices. He then mailed me a signed photograph that read: “To Jack, Sorry about the fire – Best! Paul Newman.” He remained, until his last days, one of the most generous, thoughtful and down-to-earth stars of his generation.