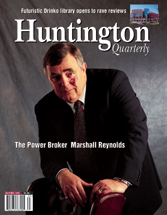

The Expanding Empire

Marshall Reynolds, the state's premier power broker, is making all

the right moves and amassing a small empire along the way.

Huntington Quarterly, Autumn 1998

In late October 1997, Marshall Reynolds was edging closer to finalizing a $26.5 million leverage buyout of the Railroad Division of Portec Inc., at the time the oldest listed company on the New York Stock Exchange. The division, which Reynolds eyed as a lucrative prospect for his portfolio of growing business interests, owned plants in Huntington, Chicago, Pittsburgh, New York, Montreal and Wales. Everything was in order. All that remained was a meeting with the accountants and lawyers to sign off on the final contracts.

But, just two days before the deal was set to close, Kirby Taylor, Reynolds point man on most mergers and acquisitions, received a disturbing phone call from the plant in Montreal. The Canadian facility had burned down overnight. Taylor rushed to the Tri-State Airport to catch Reynolds', who was boarding his private jet for a trip to California to close a $17.4 million deal to acquire controlling interest in a Silicon Valley bank.

“Marshall, I have some bad news,” Taylor said glumly. “The Montreal plant has burned down.”

“Is this some kind of sick joke?” Reynolds inquired.

“No sir,” Taylor replied.

Taylor was certain the news of the disaster would kill the Portec deal. He waited anxiously for a response. But Reynolds, dressed in a navy blue Hickey-Freeman suit and gnawing on a wad of tobacco, just sat in silence, staring out the plane’s oval-shaped window. Then, after nearly two minutes of reflection, he turned to Taylor and calmly instructed, “Get up there, take a look around and let’s figure out how we can make some money off of this.”

Figuring out how to make money has been the trademark of Marshall Reynolds, West Virginia’s most accomplished entrepreneur. The story of his success is fascinating. What he began in 1964 as a small printing shop with $98,000 in sales is now a publicly traded institution, Champion Industries, with $108 million in yearly revenue. Since last being profiled in the Huntington Quarterly in 1990, his empire has expanded to include interests in banking, manufacturing and real estate that today encompass 15 states, 33 cities and two foreign countries. Still, earning the respect of the establishment in Huntington is something that hasn’t come easy for the intimidating yet ultimately affable businessman.

A young kid from humble beginnings on the west side of Huntington, Reynolds went to work for Chapman Printing in the 1950s as a clean-up boy. He worked his way up to delivery boy, then salesman, and in 1964 he bought the company from his former boss. That’s when Reynolds got his first taste of what doing business as a Huntington outsider was going to be like. Seeking a modest $2,800 loan to purchase a new piece of equipment, he was turned down by nearly every bank in town. “All they cared about was my father’s name,” Reynolds later groused.

During that string of rejections, he was turned away at the First Huntington National Bank where he stormed out of the building and vowed, “I’ll own this damn bank one day.” Fifteen years later he did. Compelled by past rejections and using profits from his expanding printing business, he steadily accumulated stock in the bank and ultimately gained controlling interest in the early 1980s.

With the help of prominent Huntington attorney A. Michael Perry, whom Reynolds recruited to head up his new bank, he set out to rewrite the anti-quated banking laws in the state. The two men successfully persuaded the legislature to allow for branch banking and bank holding companies in West Virginia, and, thus, KeyCenturion Bancshares was born in 1985. Under Reynolds' direction, the newly formed holding company grew from one bank with $215 million in assets to 54 banking locations with $3 billion in assets, the largest in the state. It was 1990 and, by any estimation, Marshall Reynolds had arrived. But, he wasn’t through. Like a shark that must keep moving to survive, Reynolds needed to keep growing. Besides, his forays into banking had inspired a regional legend.

In 1993, the legend grew. After nearly 10 years of tremendous growth with KeyCenturion, Reynolds and the other stockholders elected to cash out and were acquired by Bank One. It is said that the day after the sale of KeyCenturion, the number of millionaires in West Virginia doubled. Reynolds earned his fair share, pocketing $25 million in the transaction.

With a large wad of cash in hand, Reynolds returned to his roots in printing and took his old company public. He carefully orchestrated the Initial Public Offering, and on Jan. 3, 1993, Champion Industries opened on the NASDAQ trading at $10 per share. Reynolds astutely decided to retain two-thirds of the stock, a move that would allow him to swap stock with other companies he was interested in acquiring instead of paying cash.

Since going public, Champion has gobbled up printing and office supply companies in 11 states and posted 24 consecutive quarters of greater net profit. The company has been 42nd and 190th respectively on Business Week’s and Forbes’ list of the “Best Small Companies in America.” However, in recent months the stock has tumbled because, according to industry insiders, some of the numerous acquisitions have not performed as well as projected. Reynolds isn’t worried.

“Most stocks get ahead of themselves, then correct and sometimes over-correct. Obviously we’re on the extreme back side of the pendulum. Right now, Champion is a real good buy.”

Shortly after going public with Champion, Reynolds found his way back to banking. He missed the action. But, according to Reynolds, there was more to it than that.

“I got involved in banking because I thought you could do more social good with that industry than anything else. That and because of the terrible times I had getting financing for a little horseshit printing company. That’s the root of it.”

In each of the cities Reynolds has controlling interest, the banks play an active role in the development of the region. “Banks can change things and they should take the lead in a community,” Reynolds asserts.

Over the course of five short years from 1993 to 1998, Reynolds bought his way onto the boards of banks in West Virginia, Kentucky, Ohio, Florida, Louisiana, California and Washington, D.C. All told, Reynolds is currently in control of 19 banks – officially. But unofficially – and in banks he has a non-controlling interest – nobody knows.

Reynolds formula for success in most business ventures is unique. In banking, for example, he targets undervalued institutions, ones nobody else is interested in, and turns them around. How? He starts by calling on talented people to assist him in each deal. Someone on Reynolds’ team goes into a community, studies the market, assesses the internal organization and reports back with an evaluation. If Reynolds thinks it’s a “good play,” he rounds up the necessary capital – oftentimes friends and associates come in on the deal – and secures controlling interest. His signature play is to strengthen the board of directors, streamline operations, increase community involvement and listen to customers.

The root of Reynolds’ overall success, though, is sales. His uncanny knack for selling, whether it’s a No. 7 window envelope, railroad component or complicated buyout offer, has enabled him to accumulate untold millions. It’s what catapulted him from delivery boy to plant owner, from loan reject to chairman of the board, from outsider to insider.

“If a company is struggling, more often than not it’s sales,” Reynolds explains. “They don’t know how to get enough business to bring the institution up to capacity. Sometimes it’s margin, selling the product too cheap. The boss thinks the only reason people buy products is price. People buy products that do the job. If price were the thing, Cadillacs would never be sold.”

Reynolds most recent coup involved the $10 million buyout of Ohio-based Broughton Dairy in November 1997. Reynolds then took the company public and, through a series of acquisitions, swelled the annual sales from $80 million to $200 million in less than a year. By October 1998, there was an offer on the table by Suiza Foods of Dallas, Texas, to pay $110 million for the year-old public venture. The deal is currently nearing completion, and rumor has it that Reynolds stands to pocket nearly $20 million when all is said and done. That, combined with the fortunes he has helped create for stockholders on countless other deals, has “elevated him to cult-hero status in his home state,” according to an article in The American Banker.

With so many business interests, his life has taken on a feverish pace. On a recent trip to Hammond, La., for example, Reynolds’ private jet landed at 8 p.m. where a car was waiting to shuttle him to dinner with a key stockholder in a local bank. The next morning, at 7 a.m., it was breakfast with the bank president before a 9 a.m. board of directors meeting. A master at shoring up allies, Reynolds believes the war is won before the first battle is ever fought.

During the board meeting where 12 neatly pressed men listened to report after report, Reynolds, who never completed college, sat quietly at the head of the table with his feet propped up while rhythmically tapping away on a calculator. Sometimes he scribbled notes, other times he stressed the importance of increased market share and building a stronger balance sheet.

The afternoon was spent on the telephone, meeting with an array of characters at the bank and touring one of his printing plants in nearby New Orleans. At dinner, where he enjoyed a 16 oz. steak with three pats of butter spread on top, he was joined by three businessmen from out of town. With a distinct Cajun accent, one of the men shared a colorful joke about “Boudreax and Marie,” an 18-wheeler (pronounced “wheela”) and a family of skunks. They laughed and talked a little LSU and Marshall football, but business was the main topic including Reynolds’ peculiar interest in purchasing some cotton fields in the northern part of the state.

After dinner, it was more meetings back in his room at the local Holiday Inn as well as phone calls to the West Coast and overseas until well after midnight.

But such a flurry of activity and widespread business interests begs the question – where does Reynolds find so many opportunities? How, for example, does he end up owning a bank in California? The answer is simple – reputation.

“I’ve worked with a lot of people,” notes Kirby Taylor, who has been with Reynolds the last three years. “I spent 22 years with Tenneco Inc., a $20 billion international company, and Marshall Reynolds has the best business mind of anyone I’ve ever been associated with. He is unbelievable at seeing value that no one else sees.”

Reynolds is regarded in business circles as “a real player,” a proven winner, the man with the Midas touch. He is repeatedly described as “brilliant” by his peers. Yet, he remains an enigma. The same man who lies on the ground in a $1,000 suit while playing with baby chicks is also revered as a “shrewd” and sometimes even “ruthless” negotiator. But, out of respect for his business acumen, he is often presented with potentially lucrative deals.

“My contacts call and tell me about an opportunity,” Reynolds says. “I probably get 10 calls a week. I don’t look at 90 percent of the deals. I don’t ever get involved in a business where there’s only a chance of a 50 percent profit. If I can’t see a multiple return, I don’t do it.”

Finally, there’s the matter of managing 50 or more business interests scattered throughout the country and world. The task must be daunting.

“Well, obviously I don’t stay on top of everything. I will contact the chief executive officers twice a month; if the company is struggling, I’ll communicate with them three times per week. I’m faxed reports that give me an overview of how things are operating. And I’ll fly to each of the locations whenever possible. It’s pretty simple,” he says modestly.

Even with his newly acquired interests throughout the country, Reynolds’ ties to the region remain strong. In Huntington, he not only maintains the headquarters for Champion Industries, but also owns McCorkle Machine Shop, American Babbit Bearing, Stationers and, most recently, Prichard Electric. He is also a majority owner of the Radisson Hotel. In Bluefield, W.Va., he owns Bluefield Gear, and in Gallipolis, Ohio, he controls 4,000 acres of farmland with nearly 1,000 head of Black Angus cattle.

With such phenomenal success and notoriety, Reynolds is often the subject of speculation and rumor. The latest word on the street has Reynolds interested in buying back the KeyCenturion banks he sold to Bank One in 1993. Is it true?

“Well, let me say this. Bank One has never called me and told me they were interested in selling because if they did I would try to buy them. Bank One’s mode of doing business doesn’t lend itself to smaller communities. Our mode of business does.”

And what about the rumor that Reynolds has been asked to manage a portfolio of companies, much like a mutual fund, for a large brokerage firm?

“I probably will do that next year…”

There’s a bit of irony in the fact that Marshall Reynolds acquired the railroad division of New York Stock Exchange. After all, Reynolds was the kid from Huntington, W.Va., who grew up on the wrong side of the tracks. He wasn’t supposed to cross that boundary. The banks made that perfectly clear when he went shopping for a small loan back in 1965. It’s hard for him to forget the “suits” who turned him away.

Today, the former clean-up boy at Chapman Printing owns the company and dozens of others. He can still be found most days at his humble, cluttered office in Huntington making the deals that transformed him into a multi-millionaire. His nights never seem to end, but, for Reynolds, the work is his lifeblood. “Work is only work if you’d rather be doing something else,” he says. “It’s exciting and we’re still having fun.”

But even today, after all his success and charitable contributions to the region, his name still draws the disfavor of some in Huntington. Whether they object to his irreverent style, his rebellious nature or his vast accumulation of “new money,” he is often viewed by the socialites as an outsider. But, Reynolds wouldn’t have it any other way. That’s what keeps him moving.