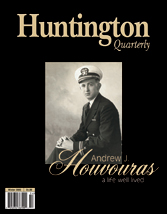

A Life Well Lived

Remembering my father who lived the American Dream and

left an indelible mark on the city of Huntington and me.

Huntington Quarterly, Winter 2005

When I was a 14-year-old freshman at St. Joseph’s High School, Billy Noe was without question the coolest kid in the school. Handsome, athletic and outgoing, he was the All-American boy every guy wanted to hang out with and every girl wanted to date. That’s why it was so surprising when we struck up a friendship. Although we shared a few classes and were teammates on the YMCA swim team (where he was a national champion and I was a mere novice), Billy was an upperclassman who could pick and choose his friends. I never understood why he befriended a lowly freshman but valued his charity nonetheless.

Early in our friendship, while I was still a bit awestruck by it all, Billy asked if he could catch a ride home with me after school. When classes ended, we waited outside for my mom to pick us up, but on that particular day it was my father who pulled up to the curb in his black and silver Ford LTD. Having Dad pick me up was a rarity and not something I had planned on. I recall feeling a bit of trepidation as he rolled down the window and said, “Let’s go.” After all, we were giving Billy Noe a ride home, and I didn’t want my father to do anything that might embarrass me.

I climbed into the front of the car, and Billy hopped in the back. I introduced my dad, and off we went. I fiddled with the radio until I found a rock station. A few minutes passed without any of us saying a word when my dad blurted out, “Turn that garbage off! I’m going to introduce you boys to some real music.” With that, he reached for his eight-track tape of Frank Sinatra and jammed it into the console. I literally slumped down in my seat as he began singing “Strangers in the Night.”

I felt humiliated as Dad continued down the road, crooning along with Ol’ Blue Eyes. But then, to my surprise, I heard Billy laughing. I turned around to see a large, approving smile on his face. He seemed to appreciate my old man’s colorful personality. I turned back around, looked over at my Dad and started laughing myself. By the time he hit Sinatra’s signature “dooby-dooby-doos,” we were all in stitches. I’ll never forget that day. It was the first time, and the last, that my father would ever embarrass me.

It shouldn’t have come as a revelation that Billy Noe liked my father. After all, most everyone who knew him liked him. It was hard not to.

I lost my father on Sept. 19, 2003. He was 84 when he died. One year later I promised myself that I would share his story with the readers of this magazine. But, September came and went and I found myself struggling to find the words. Finally, during one snowy weekend in January, I drove to the mountains, locked myself in a room and began writing. At first I felt awkward about penning a story about my father. But in time I realized he was someone this magazine would have profiled while he was alive had I not dismissed the idea as a conflict of interest. He was, in fact, one of Huntington’s most accomplished sons, and it only seemed fitting that I should write the piece, considering it was my father who first took notice of my writing ability and always encouraged me to put my beliefs down on paper.

Son of Huntington

Born in Huntington on Sept. 10, 1919, Andrew John Houvouras lived the American Dream. The son of a Greek immigrant father and an Italian-American mother, he grew up on the wrong side of the tracks. The small Houvouras home was always crowded with relatives who needed somewhere to live in the midst of the Great Depression, and he often had to share his room and his bed with one of his cousins or uncles. His father owned a small candy store on Seventh Street while an uncle ran Houvouras Grill on Fourth Avenue – an eatery many older Huntingtonians may remember.

His father, Andrew Sr., was a quiet and gentle man who immigrated to the United States from Sparta, Greece, with his three brothers when he was just 16. He loved America, especially sports. At one Marshall football game, the opponent’s running back was scoring at will and the crowd was growing angry. “Break his leg, break his back,” some of the fans shouted. “Break his little toe,” my grandfather added.

His mother was quite the opposite. Energetic, outspoken and full of life, she ran the show. When my father came home late one night after playing cards with some friends, he found both his parents waiting in the living room. “You are an hour late,” his mother barked. “Where have you been?”

“I’m sorry, Mom,” he replied. “I was playing poker with the guys and lost track of time.”

“Andy,” she said to my grandfather, “discipline that boy right now.” When all he did was administer a few half-hearted smacks, she jumped from her chair, said, “Get the hell out of the way,” and proceeded to give her son a good, stern whacking.

Dad attended St. Joe grade school and high school where the nuns took charge of his education. In high school, he was an outstanding basketball player and a starting member of the 1937 State Catholic Champions which later finished third in the National Catholic Championship in Chicago. Because of his athletic ability, he received a basketball scholarship to Marshall College where he played under the legendary Cam Henderson. Money was still tight when my father entered Marshall. To make ends meet he worked a number of jobs including selling flowers at Marshall football games. One of his other so-called “professions” was hustling pool. A natural athlete, he was one of those rare people who took to any sport or game – basketball, pool, cards, ping pong, golf, you name it.

My mom, who grew up in New England, likes to tell the story of the first time she and my father went ice skating in Huntington.

“Andy had never been on ice skates before,” she recalled. “Of course, I knew how to skate and expected he would have a difficult time on the ice. But it wasn’t long after he laced up his skates that he was out on the ice doing figure eights in the middle of the rink. It was disgusting.”

My father never claimed to be an outstanding student, preferring to say he was “street smart.” However, between all those poker games and pool halls, he did manage to earn a B.S. in chemistry in 1942 from Marshall College. But there would be no time to celebrate after graduation. America was at war.

Welcome to Newport

Following a rushed and hurried course at the Navy’s Officer Training School, my father was sent to Newport, R.I., and from there he would set sail for the South Pacific. But the weeks that preceded that ominous occasion would be filled with days of hard work and nights of drinking and dancing. It was during that time that he met Patricia Hubbard, a striking local girl with auburn hair and blue eyes. They were both good dancers and enjoyed partnering up for competitions, many of which they won.

They were married six weeks after first meeting and sometime in that brief span, my father went to see his future mother-in-law to ask for her daughter’s hand.

“Are you a college graduate?” she asked.

“Yes ma’am,” he replied.

“And you are an officer?” she inquired.

“Yes ma’am,” he said.

“Does any insanity run in your family?” she queried.

“None that I care to discuss,” he said with a smile and a wink.

My parents were married at a small Newport chapel on a hot August afternoon. My father wore his dress blues, my mother a white taffeta gown that she borrowed from a friend. He was 24; she had just turned 21. They honeymooned in New York City before saying their good-byes as Dad headed off to war.

Mom and Dad’s remarkably brief courtship was a family secret that wasn’t revealed until I was in college. Apparently, they didn’t want their children to do something foolish like rush into marriage. When I asked my parents, who were married for 59 years, how they could have been so impetuous, they both replied, “There was a war on!”

Tour of Duty

My father entered World War II as a naval gunnery officer. During his tour of duty he took part in the invasions of Africa, the Philippines, Iwo Jima and Okinawa. At Iwo Jima, he watched from his ship, the U.S.S. Estes, as the Marines raised the flag atop a blood-soaked Mount Suribachi on Feb. 23, 1945.

For three years, he served his country with distinction, only seeing my mother once during a brief assignment in San Francisco. She had taken a train cross-country to spend a few days with him before he shipped out again.

As the war in the Pacific drew to an end, the Japanese launched one last desperate strike against the United States Navy. The plan called for young pilots, many of them under the age of 18, to fly their planes laden with explosives into enemy ships in one final act of patriotism.

On April 6, 1945, the U.S.S. Estes was attacked by one of the Japanese suicide planes, or kamikazes as they were called. As gunnery officer it was my father’s responsibility to shoot down the incoming plane, which he did successfully thus saving hundreds of American lives. For his actions, he was awarded a Letter of Commendation.

My father was a proud veteran. I will never forget the Sundays at church when it would be announced that the final song would be “God Bless America.” Dad would look over at my mother and me, wink at us and belt out his own robust rendition of the song.

My mom will never forget July 4, 1976. The country was celebrating its Bicentennial, and Dad decided to throw a picnic for the entire neighborhood. At some point during the gathering, he stood up on a picnic table and led everyone in singing “America the Beautiful.”

“I can still see him standing up there singing and waving a large American flag enthusiastically,” my mother said with a laugh. “It was quite a sight.”

Back to Huntington

Following the end of the war, my father returned to Newport and his wife. The two were practically strangers, only having seen each other once since getting married.

Nevertheless, my mother packed up her belongings and moved to Huntington with her new husband. It was quite a culture shock for the young bride from Newport. The landlocked hills of Appalachia seemed a world away from her beautiful seaside home. But, she stood by her husband and in time grew to love the hills and mountains of West Virginia, where they would raise seven children.

My father went to work at the Houdaille auto bumper plant, but it wasn’t long before his entrepreneurial spirit would emerge. He began brainstorming with his brother-in-law, Leo DiPiero, about starting their own company. Although it was a risk, the two eventually quit their jobs and launched Huntington Plating Inc., a fledgling endeavor that got its start in a small building on 17th Street West. One of their first customers was the Frederick Hotel, which hired the pair to plate and polish all of the building’s toilet fixtures. It was a humble start for what would become a thriving endeavor. The business grew to include such customers as Thompson Stove, Ensign Electric and Adel Fasteners. They eventually erected their own building at 625 Monroe Avenue.

The scope of their work expanded to include chrome, nickel, cadmium, zinc and silver plating. A machine shop was added later to service the region’s mining industry.

In the meantime, both men had started families, and large ones at that. His brother-in-law Leo and sister Fee would have seven children. My parents would do the same, having four sons and three daughters – Drew, Tom, Rick, Anne, Mary, Amy and, much later in life, me. I was the unexpected surprise. My father was 46 when I was born, my mother 41.

As the families grew, so too did the business. “Necessity is the mother of invention,” my dad would always say. All told, Huntington Plating would support two large families and ultimately put 14 kids through college.

My dad took to fatherhood easily. It suited him well. He was often accused of playing favorites with some of his children and grandchildren, something he never denied. “I have an affinity for the little ones,” he confessed. “Whoever is the youngest is my favorite.”

Somehow he managed to run a successful business in between all those screaming babies and mounting grocery bills. My brothers all recall that he never missed one of their ball games. As the family grew, they eventually moved from a small apartment to a comfortable brick home on West 32nd Street near the floodwall, where they shared wonderful memories. But there were difficult times as well. When my father came home from work one afternoon, he found a distraught wife in the kitchen. “Do you know what your sons did today?” she asked.

Apparently my two oldest brothers, Drew and Tom, decided to build a raft out of branches they found along the banks of the Ohio River. Then, to test their craftsmanship, they placed my brother Rick, who was only seven at the time, on their makeshift raft and let him float down the river. It quickly fell apart, but Rick somehow managed to fight the currents and swim to shore. Upon hearing the story, my father called all three sons downstairs and proceeded to spank each one before sending them back to their rooms.

“The more I thought about it the angrier I became,” my dad would say later. “Rick could have been killed. So, I called them all back downstairs and spanked them again.”

Except on rare occasions, my father, much like his father before him, was a gentle soul. I can only recall him spanking me twice, one of which was a half-hearted attempt to appease my mother.

One of my fondest memories of my father’s gentle nature took place in January 1977. For six days we had been watching “Roots,” the highly acclaimed mini-series, as a family. At the very end of the saga, when the third generation of Kunta Kinte’s family finally found freedom and gathered on their very own plot of land, I looked over and saw a tear running down my father’s cheek. He was a sentimental man, and I loved him for it.

The Political Bug

One of the defining chapters in my father’s life came in 1960, when he learned that a charismatic young senator from Massachusetts was running for president. John F. Kennedy also happened to be a Roman Catholic, like my father, and this stoked the political fires and set the scene for a heated West Virginia primary. Religion would play a major role in the election, especially in West Virginia where less than 10 percent of the state was Catholic. Party leaders told Kennedy, who was embroiled in a close contest with fellow Democrat Hubert Humphrey, that if he could somehow manage to pull out a win in West Virginia, then the nomination would be his. The Kennedys knew what was at stake and made the Mountain State their top priority. My father, along with former college friend and business associate David Fox and businessman Bob Myers, quickly volunteered to work for the campaign.

The three men were named co-chairs of the effort in Cabell County but also worked tirelessly in other counties throughout the state.

My father left work for nearly two months to work for the campaign. He spent a great deal of time with Kennedy himself, not to mention brother Bobby and brother-in-law Sargent Shriver, all of whom visited the state regularly.

It was a bitter campaign marred by anti-Catholic sentiment. At one point during the primary, flyers were circulated that warned voters of the dangers of electing a Catholic president. Among other things, the literature stated that the Pope would run the country and that, locally, all non-Catholic infants would be castrated at St. Mary’s Hospital.

In the end, the hard work of my father, Fox, Myers and countless other volunteers helped propel Kennedy to a landmark win in West Virginia. Shortly thereafter Humphrey dropped out of the race. My parents both attended Kennedy’s inaugural festivities in Washington in 1961. After that, my dad and David Fox would see JFK three times in West Virginia. On those occasions, he would always spot them in a crowd and say warmly, “Andy and Dave, good to see you. How are things in Cabell County?”

Recently, Fox relayed a story to me that no one in my family, including my mother, had ever heard: “Several weeks after the general election, Andy learned that the man responsible for circulating those anti-Catholic flyers was in line to be appointed a federal judge,” Fox explained. “So he went to Washington to meet privately with Bobby Kennedy, who was now the United States Attorney General. When Kennedy and your father concluded their meeting, the appointment had been reconsidered.”

My father’s involvement with politics and the Kennedy family didn’t end with the 1960 primary. In the years that followed, he became active in a number of political causes.

In 1961, he was selected by Sargent Shriver as the West Virginia director of the Peace Corps. Shriver also appointed him to the national Board of Directors for the War on Poverty.

Long after the dark days that followed the Kennedy assassination, my father remained committed to the ideals left behind. Most notably, he always remembered the words Kennedy spoke during his inauguration speech: “Ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country.”

In the 1960s, my father was a member of the first Human Rights Commission in Huntington. One of the challenges in those days was to persuade local restaurants to serve black patrons. The first person my father went to see was his uncle who owned Houvouras Grill, but he was unwilling to compromise on his “whites only” policy. My father proved to be a shrewd negotiator. He knew that his uncle, a proud veteran who refused to take money from any customer who had served his country, would fold if asked the right question.

“What would you do if a veteran came into your restaurant who happened to be black?” my father asked.

“I’d serve him,” his uncle replied.

The next day Houvouras Grill began serving black customers.

Over time, my father and Sargent Shriver became close friends and in 1965 he asked my dad to take charge of the Peace Corps offices in Cyprus. He gave serious consideration to the offer but ultimately declined. He had business interests in Huntington and didn’t want to uproot his wife and seven children.

In 1966, Shriver asked my father to escort Paul Newman to various counties in West Virginia as part of the actor’s preparation for his role in the movie Cool Hand Luke. Newman spent a week in Huntington studying the dialects of people in the region by day and drinking beer and telling intriguing stories at my parents’ home at night. It was an exciting time my family will always remember fondly.

The Kennedy family left an indelible mark on my father’s political conscience, one that would stay with him for the rest of his life. In 1964, he was honored to be one of only 910 people in the nation to be interviewed by the John F. Kennedy Library regarding his insights into the Kennedy campaign and presidency.

Big A.J.

Sometime during my adolescence I coined a nickname for my father – “Big A.J.” It was meant as a compliment for the man I regarded as an astute businessman and a former political bigwig. I think he kind of liked it. For the longest time it was just a nickname that we shared. But in time it caught on with other members in our family. When my father turned 70, my brother Rick used some of his own political connections to have a racehorse named after the old man as a surprise. A year later, Big A.J. won his first race.

As the years passed, the family business continued to prosper and in the 1970s reached new heights when a second plant was constructed on Route 2. At its peak, Huntington Plating was operating two large plants and employed 120 people.

My father and Uncle Leo, who would enjoy a prosperous 57-year partnership, seemed to have the Midas touch when it came to business. Over the years, they bought interests in several local companies including Sterling Supply, C.I. Thornburg, Eastern Heights Shopping Center and Heritage Bank (now United Bank).

In 1982, they each invested $50,000 in an abandoned steel plant on the banks of the Ohio River.

“A lot of people passed on that opportunity, including me,” Fox reflected. “But not Andy. He walked the property and said, ‘Even if this deal fails, the land and the equipment will pay for itself.’”

With the help of a small group of local investors, led by Huntington businessman Bob Bunting, Steel of West Virginia re-opened its doors in 1982. Six years later it was purchased by a New York, firm and those wise enough to get in on the ground floor earned 20 times their initial investment.

“Andy was the smartest businessman I ever knew,” said Fox, who now runs an oil and gas supply business with his two sons. “He was instrumental in the formation of several companies in town. He had great instincts about people and stocks. I miss him.”

My father’s business acumen was simply an extension of the competitive nature he was born with. Whether it was basketball, cards, pool or golf, he wanted to be the best. Business was just another arena where he could prove himself.

When I decided to launch this magazine, I assembled a Board of Advisors composed of some of the city’s most influential leaders. I also asked my dad to join. At our first meeting, everyone was gathered around a large conference table when my father walked into the room. He had a presence about him, and, like the others in the room, I took notice. Even though I was 24 years old, it was the first time I had seen him in that type of setting. When he spoke, people listened.

My father was not enthusiastic about the prospect of my starting a magazine in Huntington – he wanted me to become an attorney. But after hearing me make my case to the board, he quickly changed his mind and announced in front of everyone that he thought the publication was something Huntington needed and something Huntington would support. Like many other times throughout my life, my father was there for me, offering his wisdom and encouragement.

In time, my father would retire from the world of business, but he still found numerous ways to channel his competitive fire, the greatest of which was his passion for the game of golf where his sense of fashion often set him apart. If Dad was playing golf you could spot him from a mile away. He would be the guy in the orange and red plaid slacks.

A seven handicapper in his prime, he enjoyed many battles on the links with friends like Jack Elliot, Web Morrison, Joe Heatherman, George Glasier, Chuck Whitling, Marshall Hawkins and, last but not least, Bob Beymer. Beymer was my father’s dearest friend. In many ways he was the brother my father never had. He enjoyed many rivalries with the boys on the golf course, but nothing gave him more pleasure than taking money from Beymer.

Giving Back

While golf proved to be a wonderful outlet for my father’s competitive spirit, it wasn’t enough. A few years after he retired he grew restless. Determined to give something back to the community that he loved so much, he began lending his time and talent to a number of worthwhile civic and charitable organizations.

As a member of St. Joseph Catholic Church, he served in numerous capacities. He was president of the St. Joseph Parish Council, St. Joseph P.T.O., St. Joseph Athletic Association and the board of St. Joseph High School. For all his service to his church and school, he was inducted into the St. Joseph High School Hall of Fame in 1987.

In 1986 he became involved with the West Virginia Special Olympics and was instrumental in bringing the state’s summer games to Marshall University.

In 1987, he and his cousin Ted Houvouras established the Houvouras Scholarship Fund at Marshall University. The scholarship for underprivileged students honors the four Houvouras brothers who emigrated from Greece to the United States.

In 1991, he became involved with the plight of the homeless in our community. Working with the Coalition for the Homeless, he helped raise $75,000 for an “Adopt-A-Room” campaign to help furnish the old Vanity Fair building. Regarding his role in the fundraising effort, Coalition President Betty Barrett wrote: “We’re doing well, in large part thanks to your help and dedication. You are one of the most caring people I could imagine.”

In recognition of his many accomplishments in the community, he was elected to the Huntington Wall of Fame in 1997. Two years later he was named one of Huntington’s “50 Most Influential People” by the editors of The Herald-Dispatch.

One of the things I respected most about my father was his love of Huntington and West Virginia. After he retired, he began spending more time at his second home in Florida. When his accountants advised him that he could save thousands of dollars in income taxes each year by declaring himself a resident of Florida, he refused. “West Virginia is where I made my money,” he asserted. “I don’t mind paying my fair share of taxes to a state that has been so good to me.”

Growing Old Ain’t for Sissies

My father’s wonderful ride in life began to slow down when he reached his mid-70s. A couple of health scares and the typical aches and pains of old age robbed him of some of his zeal. He tried to remain active but had already accomplished most all of his goals. And worst of all, he was struggling on the golf course. His days of winning money off of his younger pal Beymer were few and far between. He eventually gave up the game he loved so much.

“Growing old ain’t for sissies,” he often said.

The crux of the matter is that my old man didn’t like being old. He didn’t even like it when I affectionately called him “Old Man.” For someone as athletic and vital as my father, this was a difficult period in his life. He spent more and more time at church, ever devout in his faith. I suspect he knew the end was near and was coming to terms with his own mortality.

For me, the youngest of his seven children, these were trying times as well. I was resentful that the man I grew up with, who was so full of life and good humor, was changing. The man who had been a rock of strength for my family was growing more fragile with each passing year. Over time, I spent less and less time with my dad. And considering how supportive, kind and understanding he had been with me throughout my life, this was the single most selfish thing I could ever do. It is something I will always regret.

Until We Meet Again

When my parents were dating back in Newport, they would often stay out late dancing with their friends. When the evening finally ended, my dad would insist that the group gather on the sidewalk outside the Officers’ Club and sing “Until We Meet Again.” My mom always laughs when she tells that story.

On Sept. 7, 2003, my father fell at home and was taken to St. Mary’s Hospital. Twelve days later he was gone.

The night before he died I sat with him for several hours, holding his hand. I knew this would be the last time I would ever see him. I whispered into his ear and told him I was sorry that I hadn’t been a better son, but I doubt he ever heard me.

I tried to stay with him until the very end but couldn’t. As his breathing became more and more labored, I found myself unable to look at him. I left his room at 3 a.m. and drove home. He died two hours later. My sister Anne and sister-in-law Jane were at his side.

The next day my father’s picture was on the front page of the The Herald-Dispatch. The headline above the nameplate read “Huntington’s Houvouras: JFK campaign aid, businessman, civic leader dies at age 84.”

At his funeral services at St. Joseph’s Church, Monsignor Luciana spoke of my father’s many fine attributes, the greatest of which he said was his devout faith.

“I recall coming into this church numerous times over the years to find Andy praying alone. One afternoon I decided to walk over and ask him if there was anything troubling him. He said to me, ‘I don’t know if I’ve done enough, father. I just don’t know if I’ve done enough.’”

Monsignor then paused for a moment, shook his head, and said, “This was a man who had accomplished so much in his lifetime, and, in the end, all he cared about was whether or not he had done enough to please God. I must tell you that it humbled me and made me re-examine my own faith.”

Several personal effects were placed in my father’s casket, including his rosary and something he had requested years earlier – his favorite photograph taken at the beach of him and his youngest grandchild, Chelsea, with whom he shared a special bond.

When the funeral procession reached Spring Hill Cemetery, two Naval Reserve officers were waiting at the gravesite. Clad in their dress whites, they stood at attention and saluted the hearse when it arrived. As the members of my family were taking their seats for the final service, they removed the American flag that was draped across my father’s casket and folded it to tri-corners. One of the officers walked up to my mother, knelt down on one knee before her, and presented the flag. He then said, “On behalf of the president of the United States and a grateful nation, I present these colors to you in recognition of your husband’s faithful and honorable years of service to his country.”

My father would have been proud of so many things the day of his funeral – the recognition by his country for his service in the military, the articles in the newspaper and the fact that his seven children and 15 of his grandchildren were there to say good-bye. But the thing he would have been most proud of was Monsignor Luciana’s sermon that day and his description of my father as a man of great faith.

One of the many gifts my father left behind was the love he shared with his wife of 59 years. My family will never forget how much he loved our mother. We could see it in the way he looked at her, the way he spoke about her with great respect and devotion.

My dad talked often with his family about the importance of faith in our lives. And, he sometimes talked about heaven and what he thought it might be like. Looking back now, I’m sure my mother can’t help but remember those nights in Newport when Dad used to make everyone sing “Until We Meet Again.”

American Dream

My father was my hero. A proud man – proud of his Greek heritage, proud of his name, proud of his work, proud of his faith – he used to tell anyone who would listen that the Greeks had a marvelous philosophy: “Everything in moderation.” I think the thing I respected most about him was how, much like the Greeks, he achieved a remarkable balance in his life. Looking back at the legacy he left behind, I am humbled by all he accomplished and often wonder how my life will measure up.

There were many things my father taught me that will stay with me for the rest of my life. He would often look me in the eye and say, “Put God first in your life.” He enjoyed repeating the words from one of his favorite sermons when he would say, “Honor your father and your mother.” And one of the first lessons he taught me as a child was that the most important thing you have in life is your name. “Never do anything to harm that,” he explained.

Even though I only shared 38 years with my dad, I have enough warm memories to last a lifetime. I’ll never forget riding to school with him each morning listening to Artie Shaw, Glenn Miller and, yes, Frank Sinatra. I recall with great affection the encouraging letters he wrote to me in college, many of which contained a motivational quote and a $20 bill. And, most of all, I will never forget those evenings as a young boy when he would walk through the door after a long day at the office. He always had a smile on his face as he greeted me. It was my favorite part of the day.

In the weeks and months following his death, I was not burdened by the tremendous grief I had always feared as a child. Even in death, I think my father was protecting me. There were times when I could almost hear him telling me that everything would be all right and there was no reason to be sad. After all, he had lived the American Dream, left his mark on the community he loved and prepared his family for life’s many challenges. His work here was done.